From Customer-Obsessed to Idea-Obsessed: Why the Future Belongs to Companies That Can Make This Shift

The New-Age Agility In The Age of AI

The conventional digital natives wisdom that has dominated business strategy for over a decade is under pressure. While companies across industries have embraced customer obsession as their north star—following Amazon's lead in prioritizing faster, better, and cheaper solutions—I argue that this approach may actually be stifling innovation and limiting long-term growth.

The shift from customer obsession to idea obsession represents more than just a semantic change; it reflects a fundamental reimagining of how successful companies should operate in an increasingly complex technological landscape. As business models shrink from lasting decades to mere years and the pace of disruption accelerates, organizations need a new mindset for thinking about value creation and competitive advantage.

The Limits of Customer Obsession

Customer obsession, popularized by companies like Amazon, has delivered remarkable results in terms of operational efficiency and customer satisfaction. The approach emphasizes understanding customer needs, delivering superior experiences, and working backward from customer requirements to develop solutions. This methodology has proven particularly effective for digital-native companies seeking to optimize existing processes and deliver incremental improvements.

However, this customer-centric approach carries inherent limitations. Companies focused primarily on customer obsession tend to prioritize productivity gains and operational efficiencies over breakthrough innovation. The relentless pursuit of faster delivery, better service, and lower costs often channels resources toward incremental improvements rather than transformative ideas that could reshape entire industries.

The challenge becomes even more pronounced when considering that customers themselves may not fully understand what they need or want from future technologies. As history demonstrates, revolutionary innovations often emerge from possibilities that customers haven't yet imagined, requiring companies to lead rather than follow market demand.

The Case for Idea Obsession

Idea obsession—shifts focus from responding to current customer needs toward anticipating and creating future possibilities. This emphasizes curiosity, imagination, and the systematic exploration of concepts that may not yet have clear market validation but possess the potential to transform how people live and work.

Idea-obsessed organizations operate on what I call "thinking on the edges"—a framework that balances multiple dimensions of strategic thinking. This requires companies to simultaneously consider their current products and services while remaining open to influences from other industries, emerging technologies, and unexpected applications of existing capabilities.

The mindset involves looking beyond traditional industry boundaries to identify opportunities where ideas from one sector might solve problems in another. This cross-pollination of concepts often leads to breakthrough innovations that wouldn't emerge from purely customer-focused research and development efforts.

The distinction between customer obsession and idea obsession becomes clearer when examining real-world examples of both spectacular failures and unexpected successes in innovation.

Consider the case of a robotics company that attempted to revolutionize pizza delivery by cooking pizzas in moving vehicles. The concept seemed logical from a customer perspective—fresher pizza delivered faster. However, the execution failed due to a seemingly simple problem: melted cheese sliding off pizzas during transport. Despite raising hundreds of millions in funding, the company ultimately shut down due to both technical and market challenges.

The failure illustrates how customer-focused thinking can lead to solutions that sound appealing in theory but prove difficult in execution. The company focused on what customers wanted (faster, fresher pizza) without adequately considering the technical and operational realities of their chosen approach.

In contrast, successful robotics implementations often emerge from companies that take a more systematic, idea-obsessed approach. Industrial robotics manufacturers like ABB have built comprehensive ecosystems that enable their technology to work across multiple applications and industries. Rather than solving one specific customer problem, they developed flexible platforms that could adapt to various needs and contexts.

Similarly, companies like Miso Robotics have found success by learning from previous failures and building solutions that integrate effectively with existing restaurant operations. Their burger-flipping robots succeeded not because they perfectly matched what restaurant owners initially requested, but because they addressed fundamental operational challenges while fitting into established workflows.

Touchscreens

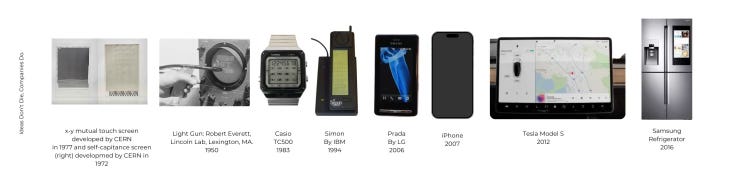

The history of touchscreen technology provides another compelling example of how breakthrough innovations often emerge from unexpected sources rather than direct customer feedback. The first capacitive touchscreen was developed at CERN in 1972, not to serve consumer electronics markets, but to solve specific control room challenges for particle accelerator operations.

The technology remained largely in specialized applications for decades before Apple transformed it into a mass-market phenomenon with the iPhone in 2007. Importantly, Apple didn't invent touchscreen technology—companies like IBM, LG, and Casio had already implemented various forms of touch interfaces. Apple's breakthrough came from reimagining how people interact with devices, combining existing technologies in ways that created entirely new user experiences.

This pattern repeats across industries: revolutionary products often combine existing ideas and technologies in novel ways rather than creating entirely new inventions from scratch. The key differentiator lies in how companies approach the synthesis and application of these existing elements.

The Accelerating Pace of Change

The urgency of adopting idea-obsessed thinking becomes more apparent when considering the accelerating pace of business model obsolescence. Research shows that the average lifespan of business models has decreased dramatically, from approximately seven to eight years a decade ago to just 3.2 years today.

This compression of business model lifecycles means companies can no longer rely on perfecting and optimizing single approaches over extended periods. Instead, they must continuously explore new possibilities and remain prepared to pivot quickly when market conditions or technological capabilities shift.

The declining lifespan of companies themselves reinforces this trend. S&P 500 companies that averaged 61 years of tenure in 1958 now last less than 18 years on average. Current projections suggest that 75% of companies currently in the S&P 500 will be replaced by 2027.

Even successful technology companies like NVIDIA demonstrate the importance of continuous reinvention. The company has transformed multiple times throughout its three-decade history, evolving from graphics processing to artificial intelligence computing. Each transformation required betting on markets that didn't yet exist—what leadership describes as investing in "zero billion dollar markets".

Building Idea-Obsessed Organizations

Transitioning from customer obsession to idea obsession requires fundamental changes in how organizations structure their thinking and decision-making processes. The "thinking on edges" framework provides a practical approach for managing this transition.

This framework operates across four key dimensions that help organizations balance current realities with future possibilities. Companies must simultaneously consider their existing products and capabilities while remaining open to influences from other industries, customer behaviors across different sectors, and emerging technologies that might disrupt traditional approaches.

The framework challenges organizations to move beyond linear thinking about their core business toward more dynamic consideration of how ideas might flow between different contexts and applications. This requires developing what some experts call "moving intelligence"—the ability to rapidly transfer learnings from one application to another.

Successful implementation also requires creating organizational cultures that support experimentation and learning from failure. Unlike customer-obsessed approaches that often focus on minimizing risk and maximizing predictable outcomes, idea obsession necessitates accepting uncertainty and viewing failed experiments as valuable learning opportunities.

The Strategic Imperative

The shift toward idea obsession reflects broader changes in how value is created in technology-driven economies. As artificial intelligence and automation increasingly commoditize traditional forms of knowledge work, human capabilities like curiosity, imagination, and creative synthesis become more valuable.

Companies that can effectively combine purpose, curiosity, and design thinking are positioned to create exponential value rather than incremental improvements. This approach enables organizations to develop solutions that customers might not have known they needed while building sustainable competitive advantages through continuous innovation.

The transition doesn't require abandoning customer focus entirely. Rather, it involves expanding organizational thinking to encompass broader possibilities while maintaining strong connections to customer needs and market realities. The most successful companies will likely be those that can balance both approaches, using customer insights to inform and validate ideas while remaining open to possibilities that extend beyond current customer expectations.

As business models continue to evolve rapidly and competitive landscapes shift with increasing frequency, the ability to generate, evaluate, and implement transformative ideas may become the defining characteristic of organizational longevity. Companies that master this capability will be better positioned not just to survive but to shape the future of their industries and create lasting value for all stakeholders.

The evidence suggests that in an era of accelerating change and technological disruption, the future belongs not to organizations obsessed with serving today's customers perfectly, but to those obsessed with imagining and creating tomorrow's possibilities. The question for business leaders is not whether this shift will occur, but how quickly they can adapt their organizations to thrive in this new paradigm.